At the edge of the thinkable. And beyond / 2

© 2024 FdR

Faccia da Reporter publishes the second part of Gianluca Grossi's lecture given on 5 December 2024. Calling war a consequence of human nature is an imposture to make us believe that it is inevitable and can only be controlled by laws. Instead, the author demonstrates why war is, in fact, against nature.

Where and from what does the idea of the ethical-legal band-aid that human beings have always, mind you since Antiquity, sought to put on war arise?

It stems from the belief that war is consubstantial to the nature of human beings.Aristotle, for example, was convinced of this. If we wanted to refer to Thomas Hobbes, we would say that war is a manifestation of the state of nature in which man

is wolf to man (homo homini lupus). This certainty is derived from the objective capacity of human beings to carry out violence: human beings kill in war since they also kill in peacetime.

To recognize this predisposition to violence is to consider war an inseparable manifestation of our being in the world.

It is a moment from here to conclude that the preventive and restraining function played by the law applied to society in peacetime can have the same effect when applied to a war.

What a mistake, however!

Only a very poor, not to say absent, knowledge of human beings can push one to support it. It is true that war would not exist if human beings were not capable of violence, but it

is equally true that the ability to be violent is not what predisposes us to war.War is not the consequence of our knowing-being-violent.

Brace yourselves, I'm about to say a big one, one of my own.

War is against nature. It is, that is, a manifestation in which human beings are involved, but which goes against their nature. There is, in fact, no war gene. War is not the consequence of genetic determinism. It is not hereditary. War also does not respond to the principle of the steam pot: it does not constitute the indispensable vent for peoples' accumulated violence.

The opposite is true: human beings must be led to war, must be skillfully and cunningly prepared and then urged to go to war, persuaded to believe in war, to yield to its necessity.

It is a job to push a people and a nation to war, to push the clerks, managers, bankers, mechanics, doctors, housewives, sales clerks, lawyers, women managers, poor christs, the unemployed and the good-timers, the faithless and their mistresses, or

their lovers, it is all the same.

There is a long way to go before we are inside a war. It is imperative to build, stone by stone, what I call the ante-war monument. Only later, several times later does the human being's ability to express violence intervene.

War is a foreign body to our organism that, through subterfuge, we are pushed (persuaded) to recognize and thus accept as familiar, as a natural constitutive part of

our organism and, even more, of our being in the world.

This does not mean recognizing to human beings an innate "meekness" (Seneca), or even an original goodness (Rousseau) that war would come to corrupt and distort.

No: human beings are capable of violence and demonstrate it in all circumstances, but in this capacity should not be escorted a predisposition to war. War is not the necessary because natural continuation of the violence of which human beings are capable.

At this point you will rightly ask me: how is it possible that what is against nature has always existed and we continue to do it?

That's all I've been waiting for! It is possible since we are constantly exposed to a flawed narrative of war.

It is flawed storytelling that aizes us to the battlefields by lying about the reasons for the sacrifice we are asked to consume and that we will consume by singing, now consigned to a collective fever.

And the narrative of the war, its aftermath, is flawed. Two examples.

© Web

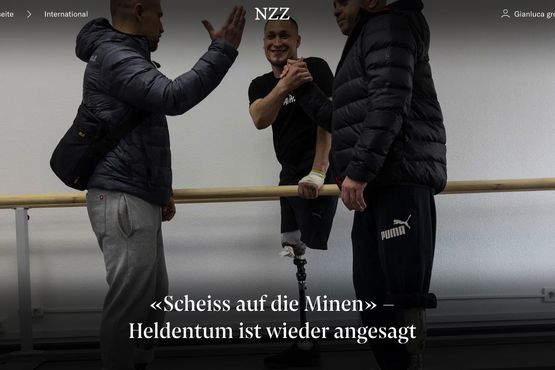

In a recent article, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) told the story of a group of Israeli soldiers who had returned from the Gaza war and were spending a "recovery" period in Switzerland, invited by some Israeli associations. The reporter asked the soldiers all but two possible questions: what did you see, what did you do in Gaza?

The NZZ did not address these two questions, the only ones that really mattered, because the soldiers' answers would have forced the audience to confront the war as it really is, not as we would like it to be.

How we would like it to be is shown by a further passage in the NZZ article. The reporter describes one of the young Israeli soldiers intent on playing Leonard Cohen's Halleluyah on the piano. This is not an insignificant detail: can you imagine this soldier unleashing himself on the battlefield in Gaza? It is difficult. In the NZZ's account - the same as

countless others - the war fades into a remote out-of-focus background.

Second example of flawed war narrative.

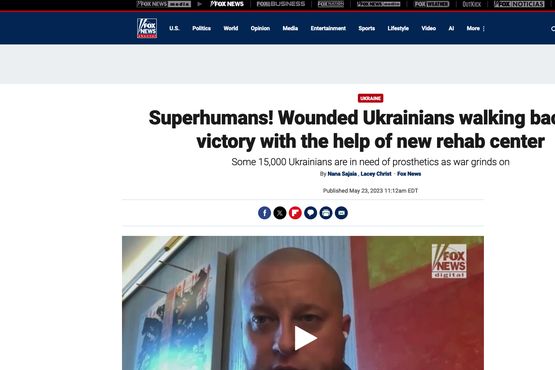

Since its inception, the conflict in Ukraine has been glorified.

European and more generally Western media have shown photographs of young Ukrainian soldiers who have returned from the front line with an arm or leg amputated.

They were photographed in color with their gleaming prosthetics-the articles explained that these soldiers were eager to start fighting again.

© Web

© Web

They were supermen, superheroes! They were, even, more beautiful and more desirable now that they had lost, thanks to the war, a piece of their body.

© Web

If this is what war is, why not have it, why stop it? Why consider it against nature?

These images were not meant to tell the story of the war, but to fuel it, to keep it alive.

Warning: the Russians did and do, for their part, exactly the same thing.

There was very little space in the press, when there was any, for veterans who returned disfigured from the front, unwatchable, with part of their heads taken away by shrapnel, without eyes, with a hole instead of a nose or on their bellies instead of intestines.

© 2024 FdR

Showing these images would have provided the most glaring contradiction to the mystifying narrative that is being produced of the war in Ukraine and of war in general: the narrative of a bearable reality by virtue of its being an expression of human nature.

What deception!

Its effect is analgesic, indeed psychotropic. It also works in the trenches.When his action fades, the human being at war understands that it is against nature for violence committed by him and suffered or seen committed by others, suffering imposed on civilians, death of women and children, fear, and hatred to take monstrous forms.

© 2024 FdR

It is another of the revelations generated by the disorientation we are dealing with.

Disoriented, bewildered precisely, the human being then plunges into a deep crisis,from which he tries to get out in two ways.

The first way: he produces more and more violence in the hope of not only staying alive but also remaining sane. He clings to the illusion that violence unleashed to the highest degree can make him immortal and forever erase from his memory the deeds done or seen done by others.

The second way to counter the crisis is this: the human being decides to prevent himself from producing further violence and chooses to give himself death, which is also the ultimate erasure of memory.

E. M. was a 40-year-old Israeli reservist soldier. After October 7, 2023, he enlisted to fight in the Gaza Strip. Upon his return home he took his own life. "E. had left Gaza, but Gaza had not left his head," a family member told the Israeli press.

UPDATE OF 2. 2. 2025: The Jerusalem Post reports that the number of soldiers who died by suicide in 2023 was 17, while in 2024 it was 21 for a total of 38. The highest number was among reservists.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline writes in the volume entitled Guerre, to which he delivers his memoirs as a soldier in World War I:

"J'ai attrapé la guerre dans ma tête. Elle est enfermée dans ma tête."

War as something that can be caught, a virus, a disease: this description corroborates my belief that war is not inscribed in our genome; on the contrary, it is an external and foreign element (against nature, in fact), from which, in a sense, we fall ill.

When the war ends, the society desires only one thing: to return healthy as soon as possible, to forget how easy it was to surrender to the slaughterhouse and erase all traces of it. Being erased is the fate that befalls veterans, this time real fate, not the fiction laced

with technicolor glory I mentioned earlier.

Francesco Ferrari wrote about it, recalling his and many of his fellow soldiers' return home from the war.

"It is a terrible impact, a fierce and tremendous scream. The daddy government, the motherland when they need your help to defend their territory, which is also yours, their freedom, which is also yours, they call you to serve the country, to fight the

enemy. (...) Then comes the long-awaited end of the war and, winner or vanquished, the military and civil authorities thank you, maybe with a nice certificate of good service and kindly dismiss you. And you leave everything there and walk out the

door like a wet chick to face a world you have forgotten. So is the veteran from a long period of war (...): everything ends and you have to face again a life that for years and years you have forgotten (...). You are like a child who must learn to walk, a person offended in body who must learn to use limbs, to speak, to write. The soldier who has returned from the war remains alone, terribly alone. I tell you this because I too have suffered the bitter experience. No one helps you because they do not understand at that moment your state of mind. And so many, too many unfortunately, end up in psychiatric clinics or in the hands of prison officers."

I have repeatedly wondered whether it is possible to have the experience of war without having been in it, I mean the experience of war as it really is, for the unrestrained unleashing that it represents.

Yes, sometimes it is possible even standing outside of it, standing peacefully at home: it is possible when of the war we perceive sudden flashes that have escaped the control exercised by what I have called its flawed narrative. It is an experience that social, i.e., nontraditional media, allows.

How do we react to this revelation? We react, seized with vertigo and embarrassment, always and only in the same way: we impute the existence of the slaughterhouse to one of the parties to the conflict, which, as it happens, is always and only the one we have taken sides against. To its inhumanity we impute the existence of the images we see. In this we are comforted and accompanied by the flawed narrative of war produced by the mainstream media.

© 2024 FdR

We refuse, therefore, to admit that this is what war is, that these are the images that war, every war produces. If it did not produce them it would be a fight, a fistfight.

How could we admit it, on the other hand? If we did, the castle of lies and hypocrisies so cleverly disguised by the pretended belief that there is another war, a war fought differently, that is, in full compliance with International Humanitarian

Law, would fall on us.

(gianluca grossi)

- to be continued -